All about the skin around the eyes and “drooping” eyelids

04/04/2025

26/07/2018

Möbius syndrome falls into the category of “rare and uncommon diseases”. In Spain, 3 or 4 babies are born with this syndrome each year.

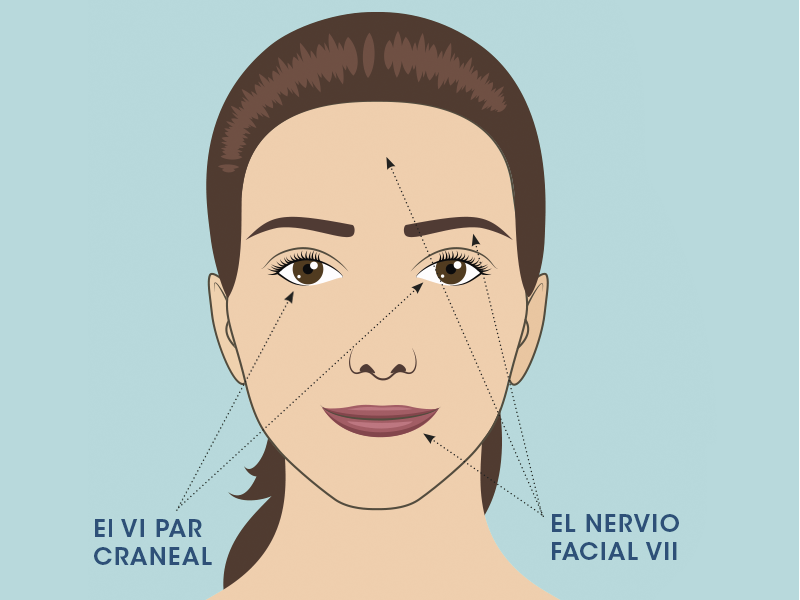

Möbius syndrome is a congenital neurological disorder, the multiple causes of which are currently unknown. It isn’t considered a hereditary disease and it usually manifests itself in isolation. What is apparent, however, is that patients who suffer from the syndrome share a common lesion: agenesis (a complete absence of development) or poor development of the nuclei of cranial nerves VI and VII, in particular (although others may be affected too). If defective, these nerves, which allow the eye and face muscles to move, cause paralysis of the affected muscles.

The facial nerve (VII) moves the musculature that controls our facial expressions (forehead, eyebrows, eyelids and lips, etc.). Paralysis of this nerve causes a “masked face”, a lack of expression and the “inability to smile”—the very definition of the disease. At eyelid level, it creates a problem with the orbicularis oculi, the muscle that closes the eyelids. Therefore, patients must take precautions concerning their eyes in order to prevent lesions due dry eye (corneal wounds and/or ulcers). Treatments include eyedrops and ointment that help lubricate the eye, humidity chambers or even surgery to protect the eyeball, depending on the case.

Cranial nerve VI is the nerve that controls the motility of the muscle that turns the eye outward also known as the abductor (the external rectus muscle), and its failure may lead to strabismus, a condition that requires check-ups and monitoring by an ophthalmologist. However, patients have normal visual acuity as the condition doesn’t have any effect on the optic nerve. If the cranial nerves are affected, speech or feeding difficulties may be observed.

During the first months of life, patients frequently suffer hypotonia (floppy baby syndrome), which clears up as the months go by. Some encounter problems with walking, breathing and, on very rare occasions, the intellectual capacity of these patients is affected.

There is no cure for the illness, although based on the information above it’s important that a range of health professionals (paediatricians, neurologists, ophthalmologists, maxillofacial specialists, traumatologists and ENT specialists, etc.) work together to treat and look after patients with the condition. And with support from educators, psychologists, speech therapists and physiotherapists, we can encourage and help them to enjoy fulfilled social and work-place integration.